How did adverts get so good at following us around?

Plus some reflections on what it means for the wider tech policy debate.

12 June 2018

We’ve all experienced an advert following us around the internet. In many cases this isn’t particularly mysterious - we’re used to web browsers remembering where we’ve been (and being able to press the back button or stay signed in to our email and social media is pretty handy), so it’s not a massive surprise that adverts seem to stick around too.

But recently things have started to feel a bit different. Ads somehow manage to keep finding you even if you turn on your browser’s incognito mode or switch devices - or in some cases are eerily prescient even when you never looked up a particular product in the first place.

The other day I shared a thread outlining some of the ways this can happen, along with a very brief reflection on targeted ads more generally. This post unpacks the discussion with the luxury of unlimited characters and lots of links to further reading. We’ll take it in two main parts - what’s going on, and whether this is ultimately a good or bad thing - and then flag some of the questions that follow in the broader policy debate on tech.

How do adverts keep on finding us?

The list of tools and techniques that makes targeted advertising possible on the internet starts with things like:

- Cookies created by the websites you visit and stored in your browser, in order to identify you when you return

- Cookies created by third party ad networks, to identify you from one site to another and display ads based on your past behaviour (aka “retargeting”)

- Cookie syncing that enables two or more different advertising systems to map the identifiers they have each assigned to a particular user, to facilitate data sharing

- Profiles associated with your online accounts that accumulate data on your searches and other activity (including your interactions with voice assistants), and then display ads based on this when you use these accounts to sign in somewhere else

- Website owners installing tracking pixels that relay your online activity back to the big online platforms, so that they can display targeted ads when you use their services

- Website owners uploading lists of customer contact information to the big online platforms, so that they can display targeted ads when you use their services

There are also more aggressive ways for ads to follow you, even if you take countermeasures like turning on private browsing (which erases your browsing history and limits cookies) or switching devices:

- Fingerprinting techniques that can identify you by matching other attributes of your system (e.g. your web browser, operating system, screen resolution, time zone, language, plugins, fonts, etc.) even if cookies are turned off and you are not signed in to any online accounts

- Associating the fingerprints of two different devices if you sign in to the same online account on both of them, so that you can be targeted later even after signing out

- Associating the fingerprints of two different devices even if you don’t sign in to the same account, by correlating their appearance on the same network at similar times

Unlike websites, apps don’t use cookies. But there are other ways for ads to follow you on your phone or tablet, including:

- Advertising IDs that uniquely identify your phone or tablet, so that ads from one app can be displayed in another app

- Associating your advertising ID with your online accounts when you use them to sign in to an app on your phone or tablet

There are even ways for ads to find you without any prior digital contact:

- Lookalike audiences that group you with other people who have similar interests or demographic attributes, and display ads based on their past behaviour

- Targeting that displays ads to people that share an internet connection (e.g. a group of flatmates sharing a broadband router)

- Targeting that displays ads to people that share a physical location (e.g. people who were in a particular place or at a particular event at the same time)

And replies to the original thread mentioned even more possibilities, including:

- Innocuous-looking hyperlinks that pass you through a tracking pixel

- Location data embedded in the photos you upload to a social network

- Unique identifiers injected into your internet requests by your ISP

- Ultrasonic beacons in stores and on TV that can be heard by apps your your phone

- Store card accounts that link your real-world purchases to your email address

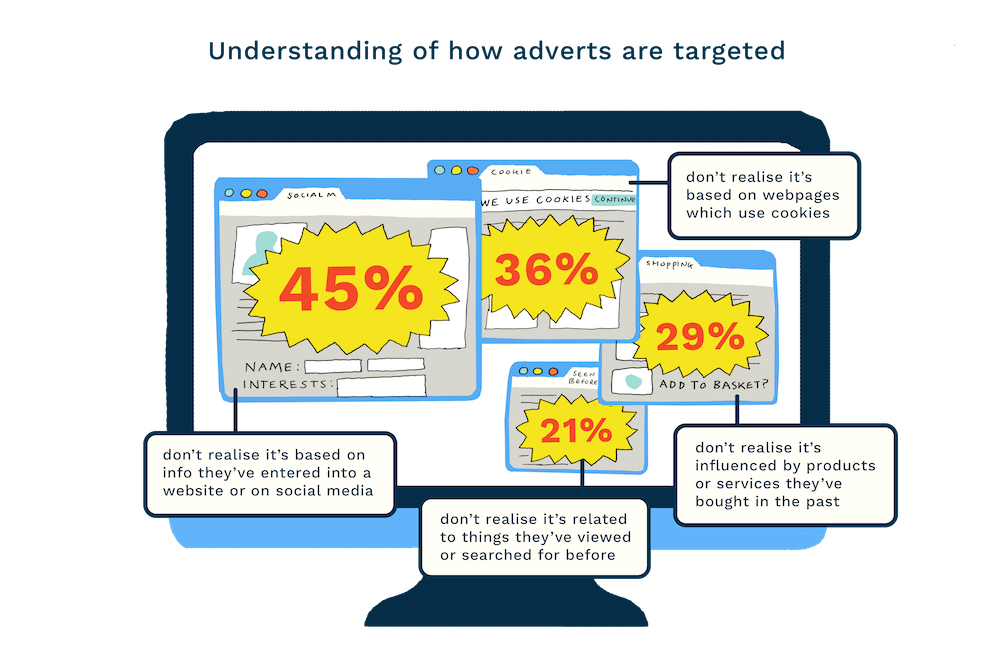

The initial reaction to a list like this is often one of horror. We all have a sneaking suspicion that there’s a degree of tracking happening - after all, how else could targeted ads work? But most people don’t realise quite how all-encompassing things can sometimes get (this is borne out by some excellent research on digital understanding from Doteveryone).

It’s worth noting that there are aspects of targeted advertising that you do have some control over, though these aren’t especially well known. For example, should you wish you can:

- Turn off ads personalisation for your Google account

- Opt out of personalised ads on Twitter

- Opt out of ads based on data from partners on Facebook

- Turn off personalised ads from participants in the AdChoices programme

- Turn off or reset the device ID on your iOS, Android or Windows phone

- Install browser extensions like Privacy Badger to block most trackers

- Use a VPN to mask your IP address

For completeness, I’m not convinced by the current wave of conspiracy theories about our phones listening to everything in order to target ads. I think it’s more likely a combination of other forms of targeting plus a human propensity to search for meaning in coincidences.

Are targeted ads a bad thing?

In the original thread I said that despite all of this, I don’t think that targeted advertising is anything like the problem it is sometimes made out to be.

For the avoidance of doubt, this doesn’t mean I think the status quo is OK, or that we should just accept it as a fait accompli. The world would be a better place with a lot more transparency about how ads are being targeted, including why a particular ad is being shown and what data informed this decision. There is also plenty of room for improvement on making sure people know when they are being tracked and have a choice about how their data is captured, stored and shared (for those of us in Europe, GDPR is a good start on this front, though I suspect most people will continue to click through data sharing and consent controls without really reading them). Both the big tech companies and those responsible for regulating them need to figure out ways to make progress on these fronts.

But I don’t think it’s as easy as concluding that all ads are bad, or that targeting is always offensive. In many cases, targeted ads are useful ads (and people are often quick to complain when they get served ads that are obviously irrelevant). Nor do I think we could force ads off the internet without incurring non-trivial collateral damage.

First, there are real products and services where the best price point for everyone is zero, because that enables the greatest number of people to participate. A platform like Facebook wouldn’t be anywhere near as useful if a significant proportion of people were priced out, or simply dropped out of the sign up process when it asked for a credit card number. Or consider news: would you be happy in a world where the only people with access to informed coverage and insight were those prepared to unlock a paywall? Of course hybrid models are possible - think paid tiers like LinkedIn Premium or Guardian Membership - but this isn’t enough to banish free, ad-supported options entirely.

Second, targeted advertising can be an effective way for new and niche businesses to find their customers. Ideas that were never viable before the internet - because you couldn’t find enough customers in your local area, or you could never match the mass-market advertising budget of your big competitors - can use carefully targeted ads to get in front of a critical mass of potential customers online. Done well this can be a good thing for consumers too, helping us to find things we value in an ocean of infinite content. So if you’re bothered about the dominance of big incumbent firms in traditional industries, it’s worth thinking about the emergence of affordable, targeted advertising as something that gives new entrepreneurs a fighting chance of breaking through to consumers.

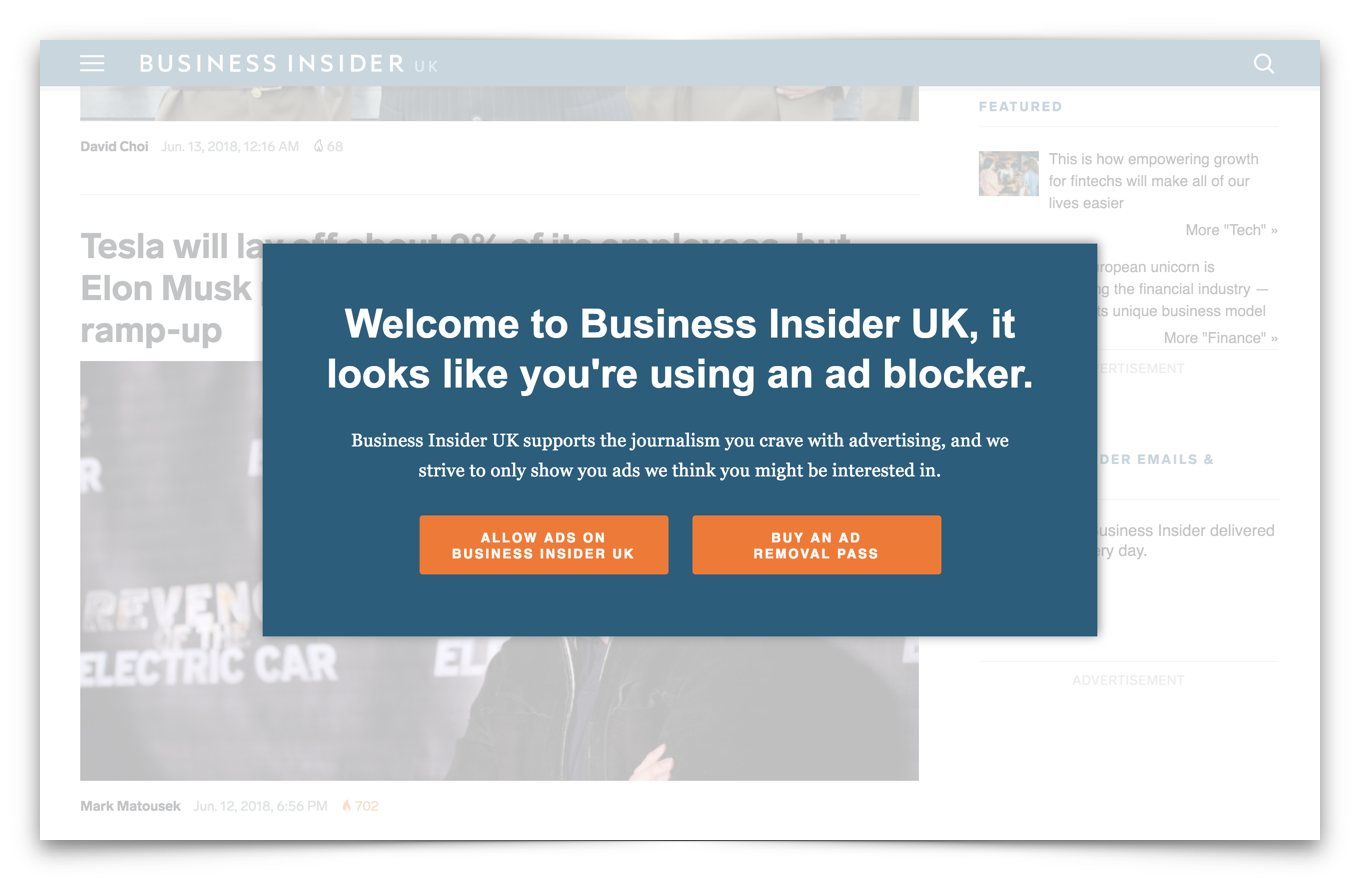

As a result, I don’t think the decision to use an ad blocker is clear cut. There’s an increasingly strong argument for them, particularly when bad ads wreck the usability of websites, serve up malicious payloads, play fast and loose with your personal data, or even hijack your browser to mine cryptocurrencies. But on the other hand, when responsible ads get caught in the crossfire it cuts off revenue for content producers and eyeballs for new businesses - and it’s unrealistic to think this won’t have consequences.

In some respects the situation reminds me of the time when universities were rife with students downloading tracks on Napster, rather than buying albums in stores. The ultimate solution to that problem was a better customer experience: first came iTunes, and then Spotify. For ads, the centralised nature of the industry - in particular around Facebook and Google - may also be the thing that saves it (and Google is already using its heft to crack down on websites that host bad ads; Ben Thompson has written a great article about this).

In any event, some element of personalised advertising has been around for a while in other contexts. The reason you see different ads in different newspapers and magazines is that they are placed there based on broad attributes that groups of readers are likely to have in common. When special offer coupons get printed for you at the supermarket checkout, you are being targeted based on your past purchases (which can be linked together between shopping trips using your store card or credit card).

But everything is a matter of degree, and it does feel like the internet has increased the intensity of targeting by several orders of magnitude. Ultimately, the thing we’re grappling with is the point at which targeted ads cross the line - and as Azeem Azhar put it to me, whether that line is drawn in pencil or in permanent marker. For those of us who remember the early days of the web, the transition from a world of infinite possibilities to an arms race with the advertising industry can feel a bit uncomfortable, even if the tracking is being done by dispassionate algorithms. But as the cliché goes, one generation’s heresey is the next generation’s orthodoxy. Maybe those that have grown up with targeted ads just won’t be as bothered?

The bigger picture

Things get more difficult when we leave the consumer arena and start to think about the broader systemic incentives facing developers, political campaigns, or even governments themselves. In this space we need to confront some important questions:

- To what extent does a desire to get eyeballs on ads contribute to some app developers hijacking our attention with notifications, or engineering addictive feedback loops that are harmful to our broader wellbeing?

- How do potentially low barriers to entry for the targeting of clickbait, fake news, negative political messages and voter suppression campaigns affect the health of our democracies and political institutions?

- How do we stop a lack of understanding about these sorts of technologies amongst our political leaders resulting in a situation where big decisions about the online world default to unelected boardrooms rather than elected assemblies?

- What is the escape route when the dual-purpose technologies that underpin targeted advertising fall into the hands of authoritarian governments determined to surveil their populations and limit their freedoms?

None of these questions have anything like an easy answer. What they do all point to is an urgent need for a far more effective and structured dialogue between those changing the world with new technologies and the policymakers and politicians that seek to govern it. This is something I’m spending a lot of time on at the moment, and there will be more to say about how policymakers should be thinking about big tech another time soon.